The following day, Easter Monday, I drove down to Athens alone to return the rented car. Along the way I caught this prospect of Olympus from the south, seen across the north Thessalian plain from the Lárisa-Tríkala road.

The following day, Easter Monday, I drove down to Athens alone to return the rented car. Along the way I caught this prospect of Olympus from the south, seen across the north Thessalian plain from the Lárisa-Tríkala road.

The following day, Easter Monday, I drove down to Athens alone to return the rented car. Along the way I caught this prospect of Olympus from the south, seen across the north Thessalian plain from the Lárisa-Tríkala road.

The following day, Easter Monday, I drove down to Athens alone to return the rented car. Along the way I caught this prospect of Olympus from the south, seen across the north Thessalian plain from the Lárisa-Tríkala road.

I was on that road because on our recent trip we had only passed by Tríkala, where a few remains are visible of the Asclepieion which Strabo called "the oldest and most famous" in Greece. (Homer has the sons of Asclepius leading a contingent from "Trikkê" to the Trojan War, Iliad 2.729-33.) I wanted to repair that omission and get a look at the place. The site is fenced all round, without even a gate anywhere, so it did not even matter that it was Easter Monday. I stuck my lens through the apertures of the chain link to get these photos of pretty much all that is there.

I was on that road because on our recent trip we had only passed by Tríkala, where a few remains are visible of the Asclepieion which Strabo called "the oldest and most famous" in Greece. (Homer has the sons of Asclepius leading a contingent from "Trikkê" to the Trojan War, Iliad 2.729-33.) I wanted to repair that omission and get a look at the place. The site is fenced all round, without even a gate anywhere, so it did not even matter that it was Easter Monday. I stuck my lens through the apertures of the chain link to get these photos of pretty much all that is there.

I also aimed to repair our earlier omission in bypassing Thebes. Just east of Thermopylae I ran into a massive traffic back-up on the coastal highway, and opted to cut over by a minor mountain road to a parallel highway to the south, running along the valley of the Kifisós. The descent into this valley afforded this prospect across it to Parnassus.

I also aimed to repair our earlier omission in bypassing Thebes. Just east of Thermopylae I ran into a massive traffic back-up on the coastal highway, and opted to cut over by a minor mountain road to a parallel highway to the south, running along the valley of the Kifisós. The descent into this valley afforded this prospect across it to Parnassus.

By the time I got to Thebes the museum had closed. (I remembered the collection as a good one, particularly the painted-pottery larnaka, small sarcophagi from the Mycenaean period; and I had read that it had been augmented and improved since we visited in 1987.) But I could still see some street-side ruins of the Mycenaean-era palace called the Cadmeion (left), the setting of much ancient tragedy; and also just a bit (right) of the Roman incarnation of the Proetidean Gate, one of the famous seven gates of the city, each of which was its own front in the war of the Seven Against Thebes. In that mythic conflict, launched by one of Oedipus' sons (and half-brothers) against the other one, this gate was assailed by Tydeus and defended by Melanippus; supposedly Tydeus wound up eating Melanippus' brains, to Athena's great disgust. The stream Ismenus nearby is now dried up, as is the fountain where Oedipus washed his hands of his father's blood.

By the time I got to Thebes the museum had closed. (I remembered the collection as a good one, particularly the painted-pottery larnaka, small sarcophagi from the Mycenaean period; and I had read that it had been augmented and improved since we visited in 1987.) But I could still see some street-side ruins of the Mycenaean-era palace called the Cadmeion (left), the setting of much ancient tragedy; and also just a bit (right) of the Roman incarnation of the Proetidean Gate, one of the famous seven gates of the city, each of which was its own front in the war of the Seven Against Thebes. In that mythic conflict, launched by one of Oedipus' sons (and half-brothers) against the other one, this gate was assailed by Tydeus and defended by Melanippus; supposedly Tydeus wound up eating Melanippus' brains, to Athena's great disgust. The stream Ismenus nearby is now dried up, as is the fountain where Oedipus washed his hands of his father's blood.

In the evening I decided to go to the Acropolis son et lumière show, since that is supposed to be the only way one can ever visit the Pnyx (where the ancient democratic assembly met); and last time we were in town I had discovered that the nightly shows were to start April 1, earlier in the year than I had expected. Nightly, however, turned out not to include the evening of Easter Monday. Still, as I was wandering around I happened on an open gate in the fence, and so got to look about the place without the distraction of the show, though only in the gathering darkness. Afterwards I perhaps foolishly attempted to find a short-cut through the park footpaths at night. Against odds I succeeded in making my way to the rather crumbling amphitheatre of the Doras Stratou folk dance troupe (which was also on this evening quite literally dark), and thence to the good old Marble House, where I was yet again staying.

Another holiday frustration awaited me the next morning in Athens: the Blegen Library was closed for Easter Tuesday. I decided to spend some of the six hours till the next bus left for Kateríni in paying a visit to the site of Plato's original Academy, which I had never done before, though I have written and published on the subject.

My way took me through a square featuring this strange monument to fallen military airmen. The presumably intended reference to Icarus seems sufficiently a reproach to these fallen, since he sinned the sin of hubris by attempting to fly too high with his artificial wings, and was duly punished for it; but far darker is the irresistable suggestion of the fall of Lucifer, the first to attempt warfare in heaven.

My way took me through a square featuring this strange monument to fallen military airmen. The presumably intended reference to Icarus seems sufficiently a reproach to these fallen, since he sinned the sin of hubris by attempting to fly too high with his artificial wings, and was duly punished for it; but far darker is the irresistable suggestion of the fall of Lucifer, the first to attempt warfare in heaven.

At the Academy site itself, such remains as there are from Plato's time are to be found a little below grade within a small park. At first I was saddened to see them so bestrewn with garbage (not to mention overgrown with weeds and nettles); but soon I grinned, thinking of the deliciously wicked possibilities for metaphoric readings of the literal fact, applicable to today's Academia.

At the Academy site itself, such remains as there are from Plato's time are to be found a little below grade within a small park. At first I was saddened to see them so bestrewn with garbage (not to mention overgrown with weeds and nettles); but soon I grinned, thinking of the deliciously wicked possibilities for metaphoric readings of the literal fact, applicable to today's Academia.

Further though subtler ironic possibilities arise for the readers of Plato's Republic from these initials formed of marble strips inlaid in the park walkway at its entrance (left). They stand for Dêmos Athênaiôn, loosely translatable as "Municipality of Athens," but more literally "the populace of the Athenians," here laying claim to the very turf where its claim to political sovereignty--the political principle of dêmokratía--was so eloquently repudiated. When one contemplates the same initials on the nearby waste receptacle rusting and otherwise neglected by that very populace, the ironies start to interact until the mind fairly reels. Perhaps, at that, the old place is still serving Plato's purposes, as he was nothing if not a master ironist, and making the mind reel thereby was where his genius as an educator largely lay.

Further though subtler ironic possibilities arise for the readers of Plato's Republic from these initials formed of marble strips inlaid in the park walkway at its entrance (left). They stand for Dêmos Athênaiôn, loosely translatable as "Municipality of Athens," but more literally "the populace of the Athenians," here laying claim to the very turf where its claim to political sovereignty--the political principle of dêmokratía--was so eloquently repudiated. When one contemplates the same initials on the nearby waste receptacle rusting and otherwise neglected by that very populace, the ironies start to interact until the mind fairly reels. Perhaps, at that, the old place is still serving Plato's purposes, as he was nothing if not a master ironist, and making the mind reel thereby was where his genius as an educator largely lay.

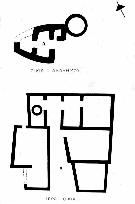

The earlier stuff nearby is better protected, with a locked shed. The plaque just within its chain-link fencing bears the site-plan shown left, and reads in its own English translation:

The earlier stuff nearby is better protected, with a locked shed. The plaque just within its chain-link fencing bears the site-plan shown left, and reads in its own English translation:

"Between the years 1955-1963 during excavations these important ancient buildings have been uncovered:

A) Foundation of Early Helladic building (2.300-2.200 B.C.) semielliptical in shape. It is consisted from prodomus main room (chamber) and a rear room (opisthodomus). At the NE corner a pit is found filled with Early Helladic sherds.

B) Sacred house (hiera oikia) (Geometric period 8th centuru BC). It is constructed in mud brick and is consisted fro seven rooms and a hall. In the interior and outside remains of sacrifices have been found.

The excavator Ph. Stavropoullos considered that the Early Helladic building was the settlement of the founder of the area, the hero Akademos, while the sacred house was used for the continuation of the same worship [i.e., Akademos' hero-cult] during the Geometric period."

Of course, these resonant identifications could be little or nothing more than wishful thinking. The photos here show (left) building A from the north and (right) the eastern half of building B from the south.