Olympia, Greece, Wednesday evening, 4 April 2001

When we left Sparta yesterday morning we traveled a spectacular mountain road high on the side of Mount Taíyetos, to Kalamáta: at many places the road was actually notched into the mountainside so that there was rock overhead and on our right but open space on our left. From Kalamáta we made our way to Pylos. In the evening our weather finally started to improve, though at first the sunshine shared the sky with dark clouds in the opposite quarter, as in these photos of the town. (The rightmost of them shows a wide-spreading old plane tree in the harbor-side square, photographed from our hotel balcony.)

When we left Sparta yesterday morning we traveled a spectacular mountain road high on the side of Mount Taíyetos, to Kalamáta: at many places the road was actually notched into the mountainside so that there was rock overhead and on our right but open space on our left. From Kalamáta we made our way to Pylos. In the evening our weather finally started to improve, though at first the sunshine shared the sky with dark clouds in the opposite quarter, as in these photos of the town. (The rightmost of them shows a wide-spreading old plane tree in the harbor-side square, photographed from our hotel balcony.)

Pylos is also known by its Italian name as Navarino, which it lent to the major naval battle associated with the war of independence, in which British and French naval forces joined (soon after the Napoleonic wars) to expel the Turkish and Egyptian fleets from Greece, a mission they were supposed to accomplish without such a pitched battle. The photo at left shows Larissa before a monument acknowledging the nation's debt to the western European admirals. The monument is flanked by two old bronze cannon that one cannot help calling the Guns of Navarino. The thirty-two-pounder on the left appears to be Turkish or Egyptian, to judge from the crescent emblem and arabic writing, while the forty-eight-pounder on the right bears the winged lion with book that signifies St. Mark and Venice. The photo at right, taken this morning in today's beautiful weather, shows the bay where the battle was fought. The far side of the bay is formed by the long island of Sphacteria, which together with the old city and the bay itself was the site of another notable conflict in 425 B.C., detailed in Thucydides; its outcome placed Sparta in the extremely unaccustomed position of having to worry about a considerable number of their Spartiate elite having been taken alive and being held prisoners of war.

Pylos is also known by its Italian name as Navarino, which it lent to the major naval battle associated with the war of independence, in which British and French naval forces joined (soon after the Napoleonic wars) to expel the Turkish and Egyptian fleets from Greece, a mission they were supposed to accomplish without such a pitched battle. The photo at left shows Larissa before a monument acknowledging the nation's debt to the western European admirals. The monument is flanked by two old bronze cannon that one cannot help calling the Guns of Navarino. The thirty-two-pounder on the left appears to be Turkish or Egyptian, to judge from the crescent emblem and arabic writing, while the forty-eight-pounder on the right bears the winged lion with book that signifies St. Mark and Venice. The photo at right, taken this morning in today's beautiful weather, shows the bay where the battle was fought. The far side of the bay is formed by the long island of Sphacteria, which together with the old city and the bay itself was the site of another notable conflict in 425 B.C., detailed in Thucydides; its outcome placed Sparta in the extremely unaccustomed position of having to worry about a considerable number of their Spartiate elite having been taken alive and being held prisoners of war.

What chiefly drew me to this southwest portion of the Peloponnese, however, was the Mycenaean palace that we visited this morning, about 30 kilometers north from modern Pylos, at Epáno Eglianós. My uncle bore a hand in its excavation, which yielded enough Mycenaean "Linear B" writing (in the relatively unexciting form of inventory documents) to permit the cracking of that ancient code in 1952. This palace inevitably came to be identified with Nestor's "sandy Pylos," the site featured in Book III of Homer's Odyssey; and apart from the obvious cautions against confusing epic poetry with history there seems little reason to cavil with this: centers of power in the Mycenaean "palace culture" were clearly far fewer in number than the poleis that eventually succeeded them, so if the Homeric bard(s) had in mind a specific Mycenaean palace on the southwest coast of the Peloponnese, this was presumably it. And there is a harmless pleasure in imaging oneself to be standing in the portico hall where Telemachus would have been brought in to the megaron, and before the very tub where he might have had that bath which the wonderful Homeric code of hospitality demanded should be offered, along with a dinner, before the guest was even asked his name.

What chiefly drew me to this southwest portion of the Peloponnese, however, was the Mycenaean palace that we visited this morning, about 30 kilometers north from modern Pylos, at Epáno Eglianós. My uncle bore a hand in its excavation, which yielded enough Mycenaean "Linear B" writing (in the relatively unexciting form of inventory documents) to permit the cracking of that ancient code in 1952. This palace inevitably came to be identified with Nestor's "sandy Pylos," the site featured in Book III of Homer's Odyssey; and apart from the obvious cautions against confusing epic poetry with history there seems little reason to cavil with this: centers of power in the Mycenaean "palace culture" were clearly far fewer in number than the poleis that eventually succeeded them, so if the Homeric bard(s) had in mind a specific Mycenaean palace on the southwest coast of the Peloponnese, this was presumably it. And there is a harmless pleasure in imaging oneself to be standing in the portico hall where Telemachus would have been brought in to the megaron, and before the very tub where he might have had that bath which the wonderful Homeric code of hospitality demanded should be offered, along with a dinner, before the guest was even asked his name.

At left, the throne room, and a detail of the circular hearth showing distinct traces of the painting scheme; at right, a modern artist's rendering of the room as originally finished.

At left, the throne room, and a detail of the circular hearth showing distinct traces of the painting scheme; at right, a modern artist's rendering of the room as originally finished.

The children found that the palace was inhabited, even after the hundred Greek and several dozen British high-schoolers had mercifully departed. Their wait for a resident's reappearance from his little hole in the foundations was in vain; but we saw his brother and fellow-inheritor of the estate of Neleus a little later on, on our way to view the tholos tomb nearby. (We had a few days before seen the great grand-daddy of such tholos or "beehive" Mycenaean tombs at Mycenae itself, the clearly wrongly so-called "Treasury of Atreus.")

The children found that the palace was inhabited, even after the hundred Greek and several dozen British high-schoolers had mercifully departed. Their wait for a resident's reappearance from his little hole in the foundations was in vain; but we saw his brother and fellow-inheritor of the estate of Neleus a little later on, on our way to view the tholos tomb nearby. (We had a few days before seen the great grand-daddy of such tholos or "beehive" Mycenaean tombs at Mycenae itself, the clearly wrongly so-called "Treasury of Atreus.")

Though proverbially ephemeral, the little wildflowers at the site may well be a better visual link with the place that received Telemachus than the mud-stained stone foundations of the palace itself.

Though proverbially ephemeral, the little wildflowers at the site may well be a better visual link with the place that received Telemachus than the mud-stained stone foundations of the palace itself.

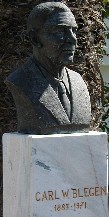

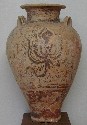

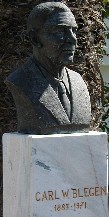

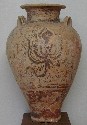

Minnesota archaeologist Carl Blegen is honored with a bust outside the associated museum in nearby Chóra. (My library away from home, in Athens, is named for him, as is a street in Chóra.) One of the pieces that caught my eye inside was this three-handled pithos with octopus. The shared fondness for this motif in vase-painting seems to me one of the most vividly obvious links between Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.

Minnesota archaeologist Carl Blegen is honored with a bust outside the associated museum in nearby Chóra. (My library away from home, in Athens, is named for him, as is a street in Chóra.) One of the pieces that caught my eye inside was this three-handled pithos with octopus. The shared fondness for this motif in vase-painting seems to me one of the most vividly obvious links between Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.

Olympia, Greece, Thursday afternoon, 5 April 2001

This morning we set out on foot from our hotel to see the sanctuary of Zeus, which ranks with Delphi as one of the larger and more striking of the archaeological sites of classical Greece. Both were major sanctuary complexes set at some little distance from actual workaday cities, and this may have something to do with it. This one is best known as the original home of the Olympic Games, and of the chryselephantine (gold-and-ivory) statue of Zeus by Pheidias, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world and the centerpiece of the central temple here. (Like the rest of the seven wonders except the Great Pyramid, it perished long before our time, in this case by fire in Constantinople, A.D. 475.) We started our tour with the Palaestra, very photogenic with lots of Doric and Ionic columns standing amid the flowering trees.

This morning we set out on foot from our hotel to see the sanctuary of Zeus, which ranks with Delphi as one of the larger and more striking of the archaeological sites of classical Greece. Both were major sanctuary complexes set at some little distance from actual workaday cities, and this may have something to do with it. This one is best known as the original home of the Olympic Games, and of the chryselephantine (gold-and-ivory) statue of Zeus by Pheidias, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world and the centerpiece of the central temple here. (Like the rest of the seven wonders except the Great Pyramid, it perished long before our time, in this case by fire in Constantinople, A.D. 475.) We started our tour with the Palaestra, very photogenic with lots of Doric and Ionic columns standing amid the flowering trees.

The Doric columns of the Heraion (temple of Hera) recall those of the temple of Apollo at Corinth, as is not surprising since this is another of the oldest Doric temples around, dating from about 600 B.C. These columns are built of stacked drums, however, in contrast with the monolithic columns at Corinth.

The Doric columns of the Heraion (temple of Hera) recall those of the temple of Apollo at Corinth, as is not surprising since this is another of the oldest Doric temples around, dating from about 600 B.C. These columns are built of stacked drums, however, in contrast with the monolithic columns at Corinth.

Naturally the children had to try the starting blocks at the original Olympic stadium, using the starting stance we had learned from the museum at Nemea: standing, with toes in both grooves, so that the feet are oddly close together.

Naturally the children had to try the starting blocks at the original Olympic stadium, using the starting stance we had learned from the museum at Nemea: standing, with toes in both grooves, so that the feet are oddly close together.

At the center of the sanctuary or Altis stood the temple of Zeus, a work of the fifth century B.C. in the Doric style. In length and width this temple was very slightly smaller than the Parthenon, but it had much more massive Doric columns (interpret that how you will), and fewer of them--six by thirteen (total thirty-four) columns in the peristyle here, as compared with eight by seventeen (total forty-six) for the Parthenon.

At the center of the sanctuary or Altis stood the temple of Zeus, a work of the fifth century B.C. in the Doric style. In length and width this temple was very slightly smaller than the Parthenon, but it had much more massive Doric columns (interpret that how you will), and fewer of them--six by thirteen (total thirty-four) columns in the peristyle here, as compared with eight by seventeen (total forty-six) for the Parthenon.

Equally enormous is this two-faced triglyph block, from a corner of either the peristyle architrave or the cella frieze.

Equally enormous is this two-faced triglyph block, from a corner of either the peristyle architrave or the cella frieze.

At left, the Bouleuterion; at right, the south stoa.

At left, the Bouleuterion; at right, the south stoa.

In the museum we admired the Nike of Paeonius (left), and the fourth-century-B.C. Hermes of Praxiteles (right), in which the young god rests a bit while taking the yet younger god Dionysus to the nymphs who will raise him.

In the museum we admired the Nike of Paeonius (left), and the fourth-century-B.C. Hermes of Praxiteles (right), in which the young god rests a bit while taking the yet younger god Dionysus to the nymphs who will raise him.

My favorite piece of sculpture in the whole museum, though, was the head of the central figure, Apollo, from the west pediment of the temple of Zeus, carved according to Pausanias by Alcamenes. Invisible to the participants, he decides the battle between Lapiths and Centaurs in favor of the former.

My favorite piece of sculpture in the whole museum, though, was the head of the central figure, Apollo, from the west pediment of the temple of Zeus, carved according to Pausanias by Alcamenes. Invisible to the participants, he decides the battle between Lapiths and Centaurs in favor of the former.

Metopes from the cella (inner) frieze of the temple of Zeus showed the Twelve Labors of Heracles. Much the best preserved is number twelve here: Heracles, with assistance from Athena (left), who applies a cushion, holds up the sky so that Atlas (right), whose regular duty this is, can fetch for him the golden apples of the Hesperides.

Metopes from the cella (inner) frieze of the temple of Zeus showed the Twelve Labors of Heracles. Much the best preserved is number twelve here: Heracles, with assistance from Athena (left), who applies a cushion, holds up the sky so that Atlas (right), whose regular duty this is, can fetch for him the golden apples of the Hesperides.

The theater, a fair hike in another direction, is clearly a modern building in the classical Greek shape. It is smaller than that at Epidaurus and has a mere four staircases through the seats, but interestingly here too one could form the pentagram on the orchestra with one point at the bottom of each staircase. Very likely this was built in deliberate imitation of that at Epidaurus. In the cavea are iron tower frameworks for stage lights, which seem as inappropriate and even sacrilegious as light towers at Wrigley Field: Greek tragedy, like baseball, should wherever possible be naturally (and brilliantly) lit.

The theater, a fair hike in another direction, is clearly a modern building in the classical Greek shape. It is smaller than that at Epidaurus and has a mere four staircases through the seats, but interestingly here too one could form the pentagram on the orchestra with one point at the bottom of each staircase. Very likely this was built in deliberate imitation of that at Epidaurus. In the cavea are iron tower frameworks for stage lights, which seem as inappropriate and even sacrilegious as light towers at Wrigley Field: Greek tragedy, like baseball, should wherever possible be naturally (and brilliantly) lit.

previous entry

next entry

main/ToC page

Pylos is also known by its Italian name as Navarino, which it lent to the major naval battle associated with the war of independence, in which British and French naval forces joined (soon after the Napoleonic wars) to expel the Turkish and Egyptian fleets from Greece, a mission they were supposed to accomplish without such a pitched battle. The photo at left shows Larissa before a monument acknowledging the nation's debt to the western European admirals. The monument is flanked by two old bronze cannon that one cannot help calling the Guns of Navarino. The thirty-two-pounder on the left appears to be Turkish or Egyptian, to judge from the crescent emblem and arabic writing, while the forty-eight-pounder on the right bears the winged lion with book that signifies St. Mark and Venice. The photo at right, taken this morning in today's beautiful weather, shows the bay where the battle was fought. The far side of the bay is formed by the long island of Sphacteria, which together with the old city and the bay itself was the site of another notable conflict in 425 B.C., detailed in Thucydides; its outcome placed Sparta in the extremely unaccustomed position of having to worry about a considerable number of their Spartiate elite having been taken alive and being held prisoners of war.

Pylos is also known by its Italian name as Navarino, which it lent to the major naval battle associated with the war of independence, in which British and French naval forces joined (soon after the Napoleonic wars) to expel the Turkish and Egyptian fleets from Greece, a mission they were supposed to accomplish without such a pitched battle. The photo at left shows Larissa before a monument acknowledging the nation's debt to the western European admirals. The monument is flanked by two old bronze cannon that one cannot help calling the Guns of Navarino. The thirty-two-pounder on the left appears to be Turkish or Egyptian, to judge from the crescent emblem and arabic writing, while the forty-eight-pounder on the right bears the winged lion with book that signifies St. Mark and Venice. The photo at right, taken this morning in today's beautiful weather, shows the bay where the battle was fought. The far side of the bay is formed by the long island of Sphacteria, which together with the old city and the bay itself was the site of another notable conflict in 425 B.C., detailed in Thucydides; its outcome placed Sparta in the extremely unaccustomed position of having to worry about a considerable number of their Spartiate elite having been taken alive and being held prisoners of war.

When we left Sparta yesterday morning we traveled a spectacular mountain road high on the side of Mount Taíyetos, to Kalamáta: at many places the road was actually notched into the mountainside so that there was rock overhead and on our right but open space on our left. From Kalamáta we made our way to Pylos. In the evening our weather finally started to improve, though at first the sunshine shared the sky with dark clouds in the opposite quarter, as in these photos of the town. (The rightmost of them shows a wide-spreading old plane tree in the harbor-side square, photographed from our hotel balcony.)

When we left Sparta yesterday morning we traveled a spectacular mountain road high on the side of Mount Taíyetos, to Kalamáta: at many places the road was actually notched into the mountainside so that there was rock overhead and on our right but open space on our left. From Kalamáta we made our way to Pylos. In the evening our weather finally started to improve, though at first the sunshine shared the sky with dark clouds in the opposite quarter, as in these photos of the town. (The rightmost of them shows a wide-spreading old plane tree in the harbor-side square, photographed from our hotel balcony.)

Though proverbially ephemeral, the little wildflowers at the site may well be a better visual link with the place that received Telemachus than the mud-stained stone foundations of the palace itself.

Though proverbially ephemeral, the little wildflowers at the site may well be a better visual link with the place that received Telemachus than the mud-stained stone foundations of the palace itself.

This morning we set out on foot from our hotel to see the sanctuary of Zeus, which ranks with Delphi as one of the larger and more striking of the archaeological sites of classical Greece. Both were major sanctuary complexes set at some little distance from actual workaday cities, and this may have something to do with it. This one is best known as the original home of the Olympic Games, and of the chryselephantine (gold-and-ivory) statue of Zeus by Pheidias, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world and the centerpiece of the central temple here. (Like the rest of the seven wonders except the Great Pyramid, it perished long before our time, in this case by fire in Constantinople, A.D. 475.) We started our tour with the Palaestra, very photogenic with lots of Doric and Ionic columns standing amid the flowering trees.

This morning we set out on foot from our hotel to see the sanctuary of Zeus, which ranks with Delphi as one of the larger and more striking of the archaeological sites of classical Greece. Both were major sanctuary complexes set at some little distance from actual workaday cities, and this may have something to do with it. This one is best known as the original home of the Olympic Games, and of the chryselephantine (gold-and-ivory) statue of Zeus by Pheidias, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world and the centerpiece of the central temple here. (Like the rest of the seven wonders except the Great Pyramid, it perished long before our time, in this case by fire in Constantinople, A.D. 475.) We started our tour with the Palaestra, very photogenic with lots of Doric and Ionic columns standing amid the flowering trees.